Move to the Isle of Wight and Training for the Raid

In May 1942, our Regiment or battalion of about 840 men was moved from the English mainland to East Cowes on the Isle of Wight for Combined Operations training behind a complete security curtain. It was a welcome change from the routine of training and our role in the defence of England. There were route marches for conditioning, speed marches in full battle gear, obstacle crossing exercises, the firing of every kind of weapon from the hip at rapid rate of fire at short range, and training to disembark from assault landing craft in nine seconds. The training was hard, and we were driven almost continually. Later, 523 men from our battalion were chosen to actually carry out our role in the Raid.

During this time, we were billeted on the grounds of Norris Castle, just outside East Cowes. Most of the men were in tents except for a few officers who had quarters in the castle itself. One warm and quite clear night, we heard the roar of planes, and a number of officers scrambled up onto the castle turret, and I followed. There was Major Lefty White in his pajama bottoms and tin hat standing with other officers watching the German bomber raid on Portsmouth which lasted for about a half hour. The search lights were trying to sight on the bombers while the ack-ack anti-aircraft guns blazed away. We think we saw one bomber knocked down. Although we were six to eight miles away across the water, we could see the flashes of bombs as they went off on impact.

On June 12th, on the first full operational rehearsal named "Yukon I", we were landed by the Navy on the Dorset coast in the morning darkness a mile off course. We were half way up the beach when someone onshore hollered, stop, you're in the middle of a minefield. We answered we might as well walk through it as back out. So we walked through it, and were lucky enough to miss them all. On the second full rehearsal named "Yukon II", which occurred on June 24th, the Navy managed to land us close to our disembarkation point.

Briefings for Operation Rutter

In the evenings after training, toward the end of June, the officers of our regiment and other regiments of the 2nd Canadian Division attended briefings on the proposed operation at a Maritime Headquarters, which we reached by crossing the inlet on the cable ferry between East Cowes and Cowes. There was a complete model of the landing sites and our regimental objectives were outlined, but at first no names to the towns were given. We were told by briefing officers surprise was to be the element that would ensure success. We were to speed or run and be on our objectives before the Germans could rouse or awake themselves, and man their defensive positions. Lt. Len Dickin and myself, both young junior officers, questioned how we were going to achieve surprise when we knew the Germans couldn't. After all, every time the moon and tide were suitable for a German crossing and landing, we increased our alert. We got no answer to our question. A naval officer told us to be quiet and not to repeat the question.

We were informed that tanks, which could provide supporting firepower, were to be landed at Dieppe proper only. We argued for landing some tanks on our beach objective, but we were told the beach rocks or shingle at Pourville wouldn't support a tank. As it turned out, the shingle at Dieppe didn't support the tanks either as they became bogged down. But the main point is that our objections were overruled by the briefing officers.

We had practiced scaling walls by hoisting one man on top of the other, but this was rather slow and impractical so in later briefings we argued for scaling ladders to climb the beach walls. It took some discussion, but scaling ladders of light steel were made and available for "Jubilee" in August, although I do not remember any being ready for "Rutter" in July.

We were also briefed that there was to be no heavy bombing of the Dieppe landing areas before disembarking because the Air Force couldn't guarantee accuracy. Civilians might be killed and rubble from bomb damage might block access to our tanks. We were annoyed because our battalion objectives required us to go up a road and straight up a very steep hill which would be rather like crossing a flat open sports field in that there would be next to no cover from enemy fire. Bombing would have created craters and provided cover. You can then leap frog from one point of cover to the next. The weaknesses in the plan, which the junior officers identified from the very first briefings, later turned out to be problems during the operation itself.

Operation Rutter Cancelled

On July 7th, we boarded the ships, and lay offshore west of Cowes ready for the actual operation code named "Rutter". However, rough weather and seas forced the cancellation of the operation. While we had been waiting for the signal to go-ahead, a German aircraft came over. It dropped a couple of bombs, one of which hit a ship in the area of the ship I was on. The bomb went straight through two decks and out the side before it exploded. So fortunately no one was injured by the explosion. After cancellation of the operation, we left the Isle of Wight, and stayed temporarily at Wykehurst Park before moving to Toat Hill tented Camp near Pulborough on the mainland. There we resumed training.

Sudden Warning of an Exercise on August 18th

One day in August out of the blue, my company commander Major John or "Mac" MacTavish called a sudden meeting or "Orders Group," and told us we were going on an embarkation exercise to practise for the second front. We were to proceed directly to Southampton carrying our G1098 stores, a reserve of ammunition normally carried on operations, but not exercises. This seemed odd, so I asked MacTavish, is everything to be operationally ready sir? He grinned yes. So I guessed we were going on an operation to Dieppe.

We arrived at harbourside in Southampton, and the ships were camouflaged this time. I boarded the Princess Beatrix along with half of our battalion; the other half boarded the Invicta. On board we were issued with new Sten guns and grenades right out of the shipping crates, so they were full of grease and needed to be cleaned. However, because we were on board ship, we couldn't fire our weapons to ensure they were working properly. We also spent the night going over the final briefing details with our men because there had been a few small changes to the plan since July. This is when the men learned they were not going on an exercise, but on operation Jubilee to Dieppe, or Pourville in our case to be more precise.

Operation Jubilee Begins

We sailed just after dark in order to avoid the daily German air reconnaissance. It was a warm quiet still night with a bit of moon and a bit of high cloud. In the early morning hours, as we steamed south, the left or east flank of our convoy bumped into a German convoy, and there was a hell of a clatter of guns and tracer fire going in all directions in the black of night. Our reaction at the time was not that we'd been seen, but that something had been seen. Yet the Germans did man and sleep in their defensive positions at Puys, a Raid objective, nearest where the convoy encounter took place.

Before long we were offshore. We climbed down from the mother ship into our Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) which carried about 110 men. In total, our battalion was carried by two LCM's and ten small Assault Landing Craft (ALC's) which each carried about 30 men. Then we were launched toward shore in the dark before dawn. It was about 5:00 a.m. in the morning on the 19th of August when we touched down. We could just make out the outline of the beach wall before us. As we moved forward up the beach, the landing craft withdrew to the convoy offshore to wait under the protective cover of a smoke screen laid down by ship and airplane.

A Description of Pourville and our Objectives

Before continuing this story, I must describe Pourville, and our objectives. Pourville is a small village lying in a valley. There is a steep headland on the west side of the valley and an even steeper headland on the east side. The River Scie runs north down the valley through the village, and empties into the English Channel. In 1942 there was a dam to hold back the river. So the village was on a long east-west isthmus of land with the sea in front and a man-made lake behind -- created by the Germans to deny freedom of movement to invading forces along this valley. There is one main street or road running east-west through the village. The road forks at the base of the east headland. One fork or road goes up and over the east headland and then descends into Dieppe, which is just under one mile distant from Pourville. The other fork or road runs south along the valley floor at the base of the east headland.

Our battalion of 523 men was divided into four companies of about 110 men, a battalion headquarters commanded by Lt. Col. Cece Merritt, a special force of about 30 men and a first aid post with stretcher bearers of about 20 men.

As we landed, the west headland and surrounding area on the right was C Company objective, Major Claude Orme, Officer Commanding. The village in front was B Company objective, Major Lefty White, Officer Commanding. The German Radio Direction Finding (RDF) Station at the cliff edge and surrounding area on the east headland was A Company objective, Captain Murray Osten, Officer Commanding. The Four Winds Farm with an artillery emplacement further inland from the RDF Station on the east headland was D Company objective, Major 'Mac' MacTavish, Officer Commanding. Special force led by Lt. Les England was to take out a German strong point at the base of the east headland which commanded the main road running east-west through the village. It should be noted that an Air Force RDF technician and a Field Security sergeant were attached to A Company for the purpose of gathering intelligence at the RDF or radar station. Our regiment was to secure these objectives so that the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders (the Camerons), who were to land after us, could proceed to objectives further inland south along the valley.

Although still a lieutenant, I was placed as 2nd in command of D Company which meant I brought up the rear of our company along with a wireless operator and two runners, one of whom was Private Stan Fisher. My job was to maintain communication between my company commander Major MacTavish and our battalion headquarters so that Col. Merritt could redirect or alter instructions as needed.

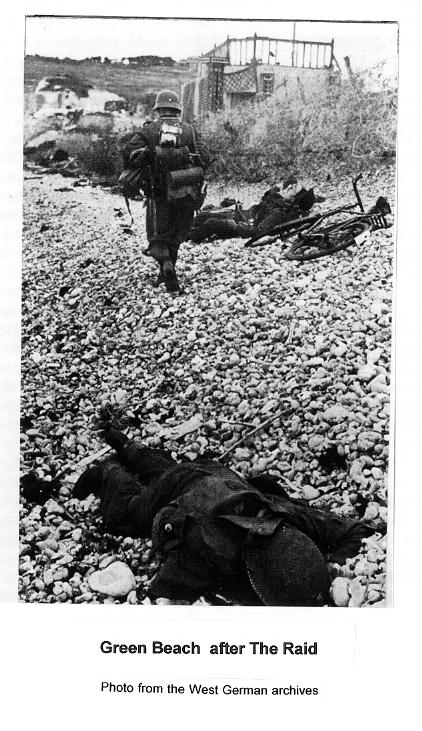

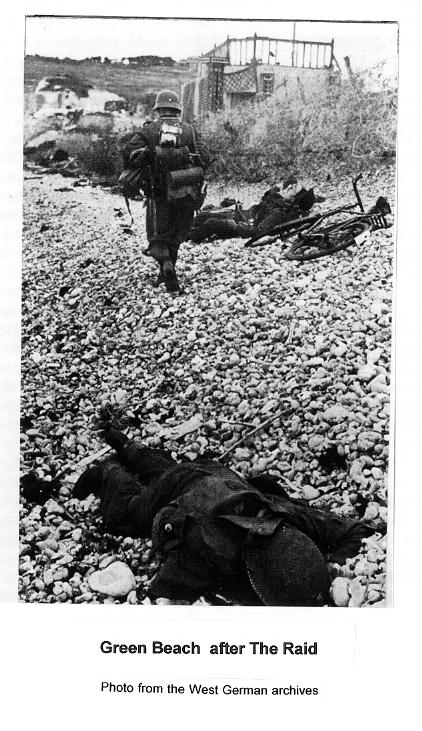

The Landing and Operations at Pourville code named Green Beach

Let me pick up the story again at the point where we touched down. The ramp of the LCM went down and we raced up the beach to the sea wall. However, we realized at the same time, that in the semidarkness, we had been landed on the wrong side or west of the River Scie. A German machine gun opened up and tracer bullets whistled along the top of the beach wall. The wall was covered in wire so I called for a bangalore torpedo which was used to destroy wire, but none was immediately at hand. So I called for a wire cutter and out of the darkness wire cutters were thrust into my hand. The message was painfully obvious, if you want the job done, do it yourself -- officers lead. I climbed the scaling ladder and cut the wire. I told the men that there was a gap between the wall and the tracer bullets which were on a fixed line of fire -- about 18 inches above the wall. Just keep low, I said, and slide over the wall and then dash for the cover behind the buildings. So over the wall I went and others followed.

Confusion reigned in the village. There were Germans and French running about. The French were shouting, don't shoot. And of course we had orders not to shoot unless we could identify a German, but it was still semi-dark. Rounding the corner of a building, I came face to face with a German and had my first experience of using a Sten gun. I pulled the trigger -- a dull thud, misfire. He must have been more surprised and nervous than I was because he didn't shoot. I ducked back around the corner and tried my Sten gun again, thud again. So I threw it away and picked up a rifle that someone had dropped on the ground in the confusion. I fired it to ensure it was in working order, and went back around the corner, but the German was gone. Later in 1944 in Normandy, I always insisted on new weapons being cleaned and fired to ensure they were in working order because your life depended on it.

It was still somewhat dark, but I found my wireless operator and runners. We went up to the main street, and found it to be under continuous machine gun fire from a pillbox or concrete position at the base of the east headland. We crouched alongside a building about a150 yards or more west of the bridge over the River Scie when I noticed a Bren gunner who was shooting at the pillbox from behind an empty gas pump or dispenser. It was one of those old fashioned pumps with a glass cylinder on top, and a hand pump at the side. I stepped behind one of the gas pumps and suggested that I spot for him, gave him the range, and said, let's try it in bursts. I watched with my binoculars his strike of shot. With adjustment he was soon peppering around the machine gun slot. That German machine gunner caught sight of us though, because bullets flew down both sides of us. We could see the sparks as the bullets hit the pavement.

Suddenly that particular pillbox ceased firing. But whether knocked out by us or some of the forward troops who stormed more than one strong point, I couldn't tell. Around this time a strange sound was carried on the sea breeze from the beach. And since forward movement along the main road near the bridge over the River Scie was bogged down, I went down to the sea wall to investigate. It was daylight now, and the Cameron Highlanders were approaching land. The strange sound was their piper playing the bagpipes. As they touched down, they were under German fire. I saw their commanding officer Lt. Col. Alfred Gostling struck down as he stepped forward from the landing craft.

When I returned to the main road, B Company was still fighting house to house on the west side of the bridge. There was German sniper fire. Half of D Company and A Company were now over the bridge. German machine gun fire and mortar fire were everywhere, but some was zeroed in right on the bridge. Bodies of our wounded and dead already lay along the 20 yards of bridge. With my crew, I set about stringing up a rope toggle bridge under the bridge as an alternate route at this bottleneck. However, Col. Merritt came back and said, it's not fast enough, go across the top. But not before there were a few words between us about the usefulness of a toggle bridge.

Major Lefty White of B Company was at the large central hotel on the north side of the road before the bridge, so I asked him to lay down some covering smoke on the bridge, which he did. My little group of four dashed across the bridge. The next thing I recalled was lying on my back on the rocks down in the ditch on the far side of the bridge. The concussion of a high explosive blast had lifted me right through the air. Two stretcher bearers were dressing a slight scalp wound. I felt my face, and it was wet with blood. I tried twice to get up, and fell each time. I had landed on the base of my spine, and there was temporary paralysis of my legs. Col. Merritt came over and told the stretcher bearers to evacuate me, but I said I'd be all right in a little while.

From here I saw Col. Merritt walk right into the face of the fire and urge the remaining men across the bridge more than once. He also picked up and carried to safety my friend Les England of Special force who was seriously wounded attacking a strong point which covered the road exiting Pourville. Later I learned Les was put aboard a landing craft that was sunk. He was then picked up by a destroyer that was bombed. He crawled out the hole in the side of that ship, and was picked up by a third ship that delivered him back to England.

Sometime later, I hobbled to the first house on the right of the road, which was a small inn or pub. A small number of A and D Company were already here including Captain Art Edmundson, 2nd in command of A Company. He contacted Col. Merritt and his Coy Headquarters, and called for artillery fire on pillboxes on the eastern slopes, but none was given. A few more joined us including Pte. M. Rogal with his anti-tank rifle. The Camerons were also starting to appear. We spotted one particular German position high on the headland in the RDF station area because their camouflage netting heaved when they fired their mortar or field gun. We poured a concentrated blast of anti-tank rifle, Bren gun and rifle onto that position to suppress their fire. We went downstairs while German fire fell on the pub in response. Then Edmundson, Rogal and other A Company men left, while I with D Company men climbed back upstairs in the pub to provide covering fire as they moved forward.

We stayed and provided covering fire for some time. However, during this period, it was slow going because if anyone wanted to move forward, the next bit of cover was already occupied by men. Moreover, any movement seen by the Germans brought down a rain of accurate mortar and machine gun fire. My wireless operator was also here, but his set was gone. We found another wireless set and twiddled the dial, but it was dead. Then we went down the road ourselves.

I reorganized the men I came upon, giving them the automatic weapons from the walking wounded who were sent back to the beach. I gave some men the task of trying to locate and eliminate snipers, and to others the task of beating down enemy mortar fire, in other words, the task of providing supporting fire for the men who were trying to reach the high ground objectives.

By this time, the focus of action had shifted to the east of the village, and to the slopes directly above, and to the right under the Four Winds Farm. Major Claude Orme and C Company, meanwhile, had successfully captured the west headland area. It became clear to Col. Merritt that D Company, despite attacking some positions, was unable to proceed further up the slope toward the Four Winds Farm. The interlocking line of German defences with wire, machine gun nests, snipers, mortar and artillery was too strong. So word was received to redeploy D Company toward A Company's objective, the RDF station area. I sent runners forward to Major MacTavish but never saw the runners again. By now the Germans had brought their artillery fully into action, and there was aircraft activity overhead. The firepower directed at us was increasing.

Meantime I bumped into Captain H.B. Carswell, the Forward Observation Officer. I tried to get him to call down naval gunfire from our destroyer Albrighton, but he refused because I couldn't pinpoint exactly where the forward line was. We had quite a heated argument. I said it couldn't matter less where the forward troops are because I know they're not within the danger area of the objective I want you to have shelled. But to no avail, the forward troops were to have no fire support.

Further attacks by A Company with Capt. Murray Osten and D Company were repulsed, with the result being that they were not able to get close enough to penetrate the RDF area or position. Nor did RDF technician Jack Nissenthall and his escort, field security Sergeant Roy Hawkins, -- their joint statements to debriefing officers after the Raid documented that because A Company could not proceed further uphill against the heavy defences, the two men attached themselves to the Camerons instead, and proceeded south inland in hope of finding an alternate route, but were unsuccessful.

I was preparing to send two sections of reorganized men forward to reinforce the A and D Company men on the slopes, when I met some of the Camerons and Capt. "Jack" or John Runcie who were at the east end of the village area. Capt. Runcie still had his wireless set, and it was on it that I contacted Col. Merritt who relayed the message "Vanquish 1030 Green Peter" which was changed to 1100 Green Peter shortly after. It meant that at 1100 hours we were to re-embark at the same place we had landed. I dispatched runners off to tell Major MacTavish, and anyone else they saw of the withdrawal order. I also contacted Capt. Edmundson of A Company, who was on the slope, by radio, and relayed the message to him. At the same time, Col. Merritt had also ordered us, and the Camerons with us, to hold the beachhead to allow time for the landing craft to come in. So we decided to go back to the pub and organize our defensive action there.

Withdrawal and Rearguard Action

I was with Capt. Ron Wilkinson of B Company by a wall near where the road forks at the east end of the village when he said he was going back. I said, wait a minute, I'll join you. Then I changed my mind. I said, watch the corner of that building you're headed toward because the Germans seem to have a direct line of fire on it. He no sooner passed the corner than fire came down hitting his hand. I believe he lost one or more fingers. The men were starting to withdraw toward the beach area now.

I made my way carefully back to the pub where there were about twenty South Saskatchewan men, and Capt. Runcie with his group of Camerons. Capt. Runcie and the other Camerons then left the pub to take up a defensive position on the west side of the village. We who remained divided into two sections of ten to cover the east side of the village. One group took up a position on the north side of the road, while those remaining with me took up our position in the pub on the south side of the road. We had a quantity of mortar, some anti-tank rifles, Bren guns with magazines and rifles of course.

So we began our rearguard action to provide cover for the troops withdrawing to the beach, and to hold back the German advance. We gave a blast on the German positions on the slopes, and at the Germans we could see moving north on bicycles along the road at the base of the east headland toward us in the village. We managed to knock a few off their bicycles, forcing the others to ground and slowing their advance.

The Germans replied with machine gun fire and mortar fire that fell directly on top of the pub. But we had run downstairs after firing. When there was a lull in their fire on the pub, we ran upstairs and fired bursts at them again which brought down more German bombardment, but we had sprinted downstairs again. The upper floor of the inn was steadily disintegrating. We continued this action for some time. It seemed a good twenty minutes since we had seen the last of our troops withdraw over the beach wall. I asked a runner to go back to Battalion Headquarters to see what the situation was there and at the beach, but he didn't return. I sent a second runner, and he didn't come back either. I asked for another runner, but nobody wanted to cross that bridge twice because there was still German machine gun and mortar fire everywhere.

I went back myself and couldn't find the Battalion Headquarters group or anyone at all. So I went down to the beach wall. There was nothing but desolation there. German aircraft were strafing, and high and low level bombing the ships and beach area. Artillery was falling. One landing craft was sunk or disabled in the water. A group of men with some German prisoners were huddled in the water behind the craft. But fire was coming from both headlands now because the Germans had reoccupied the west headland after our withdrawal. This group put their hands up to indicate they were unarmed, and attempted to get to the shelter of the sea wall, but were mowed down, the German prisoners along with our own troops. There were men lying where they were hit when they tried to leave the shelter of the sea wall, or in the water where they had tried to get into the landing craft that had come back in waves to pick men up. The Germans were trying to destroy us completely. What was worse, the last landing craft was just pulling off. The chap on board waved and shouted, sorry fellows, we've been ordered not to come in again.

Let me digress here to tell about a staff dinner I attended later, in December of 1943. After the dinner, Brigadier Churchill Mann spoke about communications and how messages are sometimes relayed incorrectly. He told a story from the Dieppe Raid of a message which was sent out to landing craft at the time of withdrawal. It read, "If no further evacuation possible, withdraw." But when relayed the "If" was omitted and the message was received as, "No further evacuation possible, withdraw." I spoke up and told about the skipper who shouted they'd been ordered not to come in again. I added it was anything but amusing or humorous to those who were on the beach.

I made my way back to the pub where I told the group of about eight men who were left to go back to the beach one at a time, and to see if they could find a way out. We could see the Germans cautiously making their way along the road. We fired our last round of mortar at them, and then the last two of us pulled out and went back to the beach.

Just Fortunate to Get Off the Beach

There were about twenty-five of us here, just west of the centre of the beach wall. An ammo count showed us we had only one magazine of Bren left, one or two rounds of mortar and some rifle. Not much and the Germans were only 300 yards away. Lt .Ven Conn from our Company came along; he had a big dressing on the side of his face. He joined us, but was captured later. I actually thought at this time that we'd been left behind. I didn't know that there were about two hundred South Saskatchewans and Camerons against the sea wall at the western side of the village because we couldn't see them along the wall because obstructions protruded at various points. Then out of the smoke from the east side, an enterprising naval chap in a small landing craft started a sweep parallel to the shore about 400 yards out. We waved, and received a wave of acknowledgment from the landing craft. It drew enemy fire, but miraculously no heavy fire hit it.

Well fellows, I said, if you want to go home, there it is. But once you leave the sea wall, if you get shot, no one stops to pick you up because anyone who stops will be shot dead. Is that understood? Yes, sir, they replied. I said, let's go then. Not a man moved. I said that landing craft is your last chance. I'm going now, let's go, and I went. It's hard to be sure but about 15 to 20 men ran to the water and waded out into the shallow water of low tide. A few men were left standing by the wall in doubt. It seemed a hell of a long way to go, almost endless, when I was being shot at. But the concentrated enemy machine gun, mortar and artillery fire claimed more of us. Not more than five or six of us got aboard.

The landing craft turned and headed straight out, bullets ricocheting off the metal sides. Even though we were told to keep our heads down under the metal bulwarks, the smell of the boat made me feel so queasy, uncaring, I stuck my head up for fresh air rather than be sick. The skipper said he didn't think this boat could make it all the way back to England so he transferred the wounded to a larger vessel, and those of us who were mobile to a large tank landing craft farther out, where we scrambled aboard up the netting. I don't remember much about that afternoon except that the anti-aircraft guns were going. After the Raid, it was reported that we lost close to 100 aircraft while the Germans reported losses of about 50. Whatever the numbers reported at the time, the losses were significant for both sides. There were craft and ships continuously going back and forth. It was dark before we landed at Newhaven.

Reception at Newhaven (Seaford) and Return to Camp

A Provost or military policeman met and directed us into a vehicle which took us to a reception centre. We went in through a blackout curtain into a building. The reception team grabbed us and questioned us. What happened? Who came back with you? Who did you see killed or wounded? I gave them the list of the men on the truck, and said briefly what I did. But as to killed and wounded, I said I saw a lot, but can't remember explicitly anything. Remember the nine hours ashore seemed like only ten minutes. And in the heat of the moment for the most part, you only register someone is hit and don't stop to register, oh, that is John Smith. As well, it was more than thirty hours since our last meal at lunch the day before. Heavens, even I was reported killed by someone who had probably seen me knocked off the road at the end of the bridge, so you can't be sure of anything. They handed me a mug of rum, but the thought nauseated me so I asked for tea and something to eat. That steaming tea and bully beef on white bread sandwich tasted better than anything I'd ever eaten.

Since nothing else was happening now, and no one could tell me what to do or expect, I rounded up the South Saskatchewan men I could find with the object of returning to camp. Our group of 29 men found a driver outside who took us back to Toat Hill Camp. It was just after midnight when we arrived back, and we found that we were the first group back. After arousing the camp, we had something to eat, and then off to bed.

The News at Home in Canada

Next day, August 20th, a CBC radio reporter named Gerry Wilmot came to our camp and interviewed us. As one of the few officers who had seen the forward positions who returned, I was interviewed and was asked to introduce several of the men including Company Sergeant Major Frank Mathers, Private Stan Fisher and Lance Corporal Rutz. (Col. Merritt, Majors MacTavish, White and Orme, Captains Osten and Edmundson and Lt. Conn had become POW's.) Our interviews were broadcast more than once across Canada. My wife Louise had become very worried as news of the operation had broken. She went downtown in Calgary where we lived and sent me a telegraph which read: Worried. Haven't heard from you in six weeks. Please write. No sooner had she returned to our apartment on 12th Avenue East than she heard the broadcast of the interviews on the radio, and she cried in relief. That's how she learned I had survived. Neighbours came by and friends phoned to tell her they had heard the news as well.

The Aftermath

Groups of people continued to come back into camp next day, the 20th of August, until there were about 210 of the 523 in camp. It soon dawned on us a lot weren't coming back. There were 143 reported wounded in hospital. And that left 171 men. It was more than two months before the Red Cross obtained a full list of prisoners of war, which numbered 89. And this meant the remaining 82 were either killed or missing in action. Slowly over the next few months replacements were drawn from the holding centre or from overseas. Training for the second front resumed.

In respect to my company, D Company, Major MacTavish, the Officer Commanding, was captured. Of the three Platoon Commanders, Lt. Ven Conn was wounded and captured, Lt. Jack Nesbitt was wounded and returned to England, but I cannot recall who was acting as the third platoon commander. Because our company was short an officer before the raid, one of several sergeants in the company would have filled this role.

In the aftermath, we were told by Battalion Headquarters to have every man write or tell about what he saw or did, and these observations were then typed up. On the basis of these reports, Battalion Headquarters would recommend those they thought were deserving of medals. Seeing the potential for self-promotion, my reaction was swift. That's no damn way to get medals in this damn army, I said. I'll recommend anyone I saw do anything worthwhile, and I will get my men to tell their stories. But don't expect me to provide one. Instead, I gave a brief report on our D Company action.

However, because I was one of the few officers who had seen the forward positions on the east side of Pourville, and who had returned, I came under pressure to corroborate the testimony others had given about the actions of a certain individual. I refused to verify anything I hadn't seen myself, but did give a second statement concerning what I had done and seen east of the bridge. I commended the actions of Capt. Arthur Edmundson ( who is not related to me despite similarity of name) on account of his calm, initiative, and well organized tactics under fire.

So not until fifty-one years later did I write my first personal account, which was produced almost entirely from memory except for verifying details like dates, numbers of casualties and the spelling of names. Now sixty-one years later, after reviewing the report and statement I gave in 1942 for the first time, I decided to revise my account to include the few aspects I had forgotten.

In respect to awards, I came to look upon medals with a jaundiced eye because some men we recommended for great deeds of courage or sacrifice in unsuccessful operations never received one, here and in Normandy, while some men received them in successful operations for good deeds that were not as outstanding. Such was the political climate within the Army in regard to medals.

A short time later, we were given a general medal which if I recall correctly was called the 1939-42 Star, and it was later renamed the 1939-45 Star so that in the end there was no specific medal for service in the Dieppe Raid -- that was still true in 1993 when this story was first written. On January 2nd 1994, the CBC presented a television program which dramatized the Dieppe Raid, and underlined the lack of recognition for the men who had served there. It provoked public pressure which led in the spring of 1994 to the announcement of the issuance of a Dieppe Clasp which conveyed recognition at last, after so many years.

In the Raid post-evaluation period, it was found that some small Canadian towns, and even individual families, had sustained multiple losses or wounds of community or family members. In our regiment there were two brothers killed, Melville and Walter Beatty, aged 23 and 22 years respectively. As a result it was decided that not all family members should be permitted to serve in the same unit in order to reduce the risk of multiple loss. My brothers Bill and Dick Edmondson served with the South Saskatchewan Regiment as well. However, my brother Dick suffered a leg and back injury during training, so under this new Army policy, he was transferred in early 1943 to Canada where he served at the Officer Training School in Brockville, Ontario until the end of the war in 1945.

Another repercussion of the Dieppe Raid was the new policy that older men over age forty were not deemed suitable for combat roles. As a result, many men throughout the army were transferred to administrative or training functions because of their age, and our battalion was no exception. If my memory is correct, Lt. Col. H.T. Kempton, Major Jim McRae and Captain Percy Jardine fell into this category.

Reflections

In retrospect, I was a young inexperienced headstrong officer - only 23 years old at the time. And I was angry about aspects of the operation. About how we were expected to gain surprise and run onto the headland enemy positions before they could rouse themselves -- an impossible task. About the lack of pre-bombing and cover. About how we were landed on the wrong side of the River Scie, the consequence being that we had to run the gauntlet on the bridge over the River Scie. About how we had to go over the bridge rather than under it on a rope. About how we had no naval, tank or artillery fire support so that we had insufficient firepower to do the tasks expected of us. One frustration was mounted on another while we came under German sniper, machine gun, mortar, artillery, high and low level bombing and strafing fire from a well organized defence. It all culminated in nine hours of horror for us.

But that's not to say Dieppe was fruitless. It's known in military circles that after this, because of the mistakes made, the D-Day assault of 1944 was planned across open beaches rather than on heavily defended ports. Moreover, there was to be full air, naval, tank and artillery support from the outset. In addition, a permanent landing fleet was maintained and procedures were refined so that landings elsewhere during the war were successful. Still we paid a heavy price for this "learning experience" which some argue should have been known already: for example, from the experience of the Dardanelles landings in Turkey during World War I.

In the opinion of some, Dieppe was a "strategic success" because it kept the threat of an Allied invasion and a western front more centred in the German mind. Thus German troops were committed to western defence, a fact which helped reduce the pressure on our Russian allies on the eastern front. Yet to me, a strategic success remains a cold comfort when measured against the suffering of the men at Dieppe, and the suffering of their families.

Pourville and Dieppe Revisited -- 1992

In August of 1992, I went back with my wife Louise and my two sons for the 50th Anniversary of the Dieppe Raid. We visited the war cemetery there. I still felt the sorrow at the loss of so many friends as I read their names on the gravestones -- some of them schoolmates and family friends, others friends made while serving in the army. My wife Louise was upset because she couldn't find the headstone for her high school classmate Private Walter Chymko from Semans, Saskatchewan. At the time, we thought his body may be one of the more than a hundred graves marked unknown, or may be one of those whose bodies were never recovered. Later, after our visit, we learned Private Chymko was buried in the Canadian Cemetery near Calais. So his body must have been carried down the coast by the ocean currents.

Nevertheless, I was heartened to see that so many French people attended the prayer vigil on the night of the 18th of August at the cemetery. In the parade of the 300 veterans next day from the cenotaph to the Dieppe City Hall, the Dieppe citizens lined the streets twelve deep. Here at least the efforts of the living, wounded and dead in the face of adversity are still cherished and kept alive. At home in Canada, at the time of the first writing of this story, few seemed to teach the younger people about our achievements which are known to few, and we seemed largely forgotten.

Since the 50th Anniversary of the D-Day landings in 1994, greater interest and honour has been expressed by Canadian citizens toward the veterans each year, as our ranks thin. More effort has been made to learn about our experiences. And more gratitude has been shown for our contribution toward creating the positive conditions, including freedom, which we enjoy today.

Copyright Permission for this web version.